A+D Exhibition: Never Built Los Angeles

A+D Exhibition: Never Built Los Angeles

Sunlaw Energy Corporation

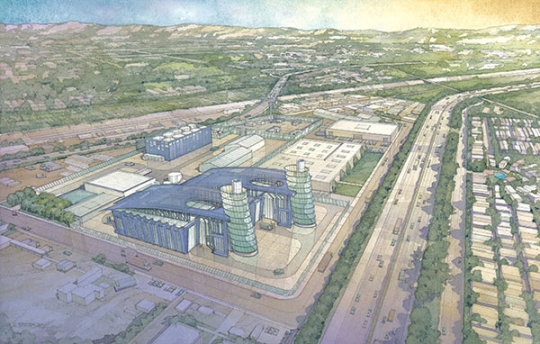

Nueva Azalea Power Plant Canopy and Enclosure

South Gate, California

With the privatization of energy companies, a positive public image is a requisite for success. As a contemporary design inquiry, the representation of the power plant in the landscape and the consequent imputed character of its products (and byproducts) raises issues both portentous and timely, ideological and ethical, regarding architectural camouflage, (in)congruity with context, and the nature of nature.

Program:

Our client, Sunlaw Energy Corporation, has invested in developing clean-energy sources to convert natural gas to electricity. It is also interested in not pretending to be something other than what it is. At the same time, the leadership of the company is enlightened and socially conscious enough to understand the imperative to discreetly cloak itself without trying to disguise itself as an overscaled bucolic farm or a simulated tree.

Zoning Constraints:

The existing power plant meets industrial zoning requirements for the site. Design constraints for the power plant require a minimum stack height of 130 feet, access to the plant engine, and 50% opacity of the structural canopy for adequate ventilation.

Location:

Sunlaw retained us to design a prototype canopy and enclosure for their case study Nueva Azalea power plant in the mixed residential-industrial neighborhood of South Gate, 7 miles southeast of downtown Los Angeles.

Process:

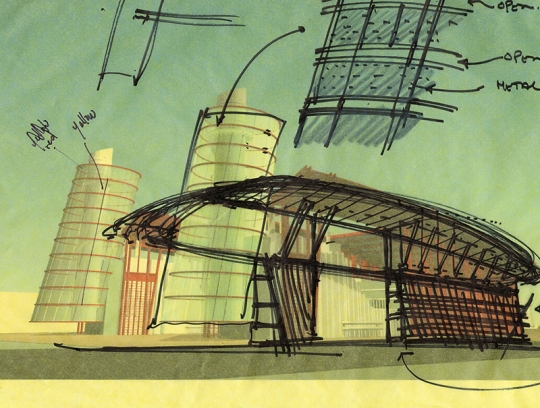

We conducted research into tower precedents—including visionary towers, towers in ancient history, towers of babel, towers as lighthouses, towers as energy source (i.e. windmills), towers as symbols, towers of information, air traffic control towers, towers as markers (campanile, city landmarks, towers as solar collectors, towers representing culture, minarets, spires, towers of light.

Solution:

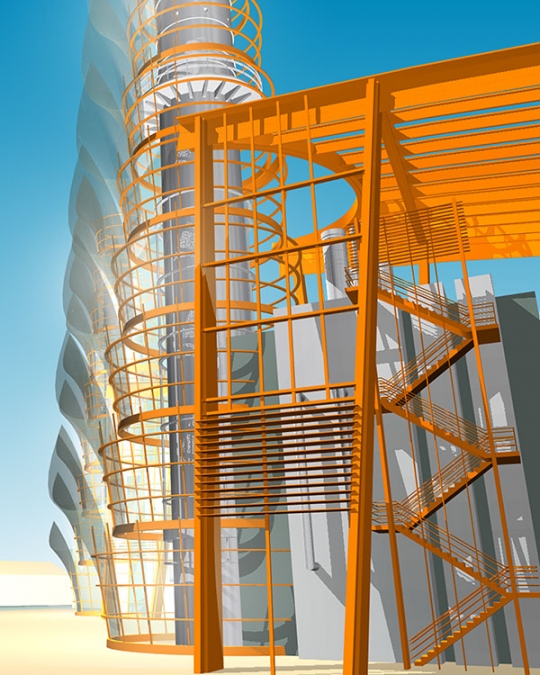

As an overall concept to unify the different parts of each plant unit, two formal schemes were merged to create the final design of the elliptical cylinder juxtaposed with the sweeping arc of steel canopy. This gesture acts to integrate the plant unit's smokestacks with its power generators and a new class of catalytic converters in one building. The two plant units are juxtaposed and staggered, so that we can see the silhouettes of two similar forms from the adjacent 710 freeway and from the surrounding streets. The skyline of the project formed by the curved and vertical elements provides a powerful symbol and landmark.

We aspired to express the plant’s function with an architecture that is honest, even celebratory rather than attempt to disguise it as has often been done elsewhere. To accentuate the visibility and reinforce the identity of the power plant, we have used high-technology, machined materials such as steel and woven-wire mesh. Since ventilation is a major concern, the sweeping arc of the canopies will have less than 50% opacity. The design has many open elements throughout to accommodate the passage of air as well as for ease of maintenance of large pieces of equipment. All the sides as well as the top of the structure have openings. The plan for the building is also splayed, to reduce the massive appearance of the structure.

The elliptical cylinders containing the stacks are poised at an angle, giving these towers an active silhouette against the sky. The leaning towers would be clad with LED-embedded glass, programmed to display art, community messages, and information about the plant to freeway drivers speeding by. A computerized lighting system animates the leaning towers, heralding the changes of seasons and events such as Halloween or the Fourth of July by the use of graphics and colors. Information about the environment and our use of energy sources can also be shown on the towers. The curved canopies reflect the distant mountain ranges surrounding the Los Angeles basin, while the rising towers evoke the dynamic imagery of Simon Rodia's famous nearby Watts Towers.

Background on Sunlaw Energy Corporation and the Nueva Azalea Project

By Robert Danziger, founder and CEO

I started Sunlaw Energy Corporation in October of 1980 to help revolutionize the power generation system that had been operating relatively unchanged since the 1930’s, in order to achieve energy independence and a clean environment coupled with prosperity for the whole world. I was the youngest CEO in the electric generation business at that time (I was 27), and I did not know it was impossible.

Sunlaw was to me a kind of sculpture, a concept that grew out of my career as a studio musician specializing in hybrid and avant-garde instruments and music. This sculpture, however, had not just physical presence, but sounds, music, ethics, social and policy attributes that required long-term profitability, deep personal community involvement, and unparalleled labor-management cooperation.

I started Sunlaw with $10,000 and a consulting contract to the Solar 100 Project. A joint venture of Southern California Edison, Bechtel and McDonnel Douglas, it was the largest solar electricity project under development in the world. This occurred two years after I joined the Jet Propulsion Laboratories energy and environmental think tank that was, at that time, the lead center for all advanced energy research in the United States. Jet Propulsion Laboratory helped me develop the concept for Sunlaw. I financed Sunlaw with consulting work, eventually having a hand in virtually every alternative energy technology, and did some level of work in 40 States and 20 countries.

In 1982 Sunlaw signed agreements with the two largest cold storage warehouses in Los Angeles to supply them with refrigeration and with Southern California Edison to sell them electricity. The refrigeration and electricity are to be supplied from power plants using jet engines burning natural gas that would operate 24 hours per day, 7 days per week. Sunlaw worked with General Electric to adapt its largest jet engine for these pioneering systems.

In 1984 Sunlaw successfully financed these two projects using a technique pioneered by Sunlaw and its investment bankers Merrill Lynch and Smith Barney. Sunlaw had no money—its only assets were the contracts and a turnkey construction contract. This “Project Financing” relied on the intersection of these contracts and a first-of-a-kind insurance policy from Lloyd’s of London to provide the security for the $62.8 million dollar loan, and to provide the return to the equity investors. The investors were 215 wealthy individuals (including musicians Prince and two members of the Jackson Five family) and the John Hancock Insurance Company.

At the time Sunlaw began operation, the average utility power plant operated less than half the time, and had an electrical efficiency of less than 30%; injuries, even deaths were commonplace. They used coal or oil as fuel, and construction costs were more than double what they are today – over 30 years later. Allowable emissions levels were over 50 times what they are today.

In its first year of operation and every year thereafter Sunlaw shattered these records, achieving over 99% availability, 50% electrical efficiency, a perfect safety record, operated solely on natural gas, and later achieved a 98% reduction in emissions using catalytic converters invented by Sunlaw.

Sunlaw achieved these records while being extremely profitable. The performance was a big part of the profitability, but an even bigger part was the bet Sunlaw made that natural gas prices would go down and stay down. This bet was made based on work done at JPL in 1977 that accurately predicted the vast supply of natural gas that now, in 2013, is widely known, but was counter to conventional wisdom of the 1980’s. The Sunlaw power plants were designated “Pioneering” alternative energy plants by the California Public Utility Commission.

These operational and profitability records were widely observed by the power industry. Over the next 30 years, imitation of the Sunlaw design has had, by a wide margin, the biggest energy conservation and emissions reduction effect since the dawn of the industrial revolution, and is now starting to replace coal-fired generation in many states.

Combined with Sunlaw’s special catalytic converters, the Sunlaw plants were the first to actually eliminate an entire class of pollutants—carbon monoxide. In addition less than half the toxic particles in the air that went in to the Sunlaw plant came out of the smokestack—an actual vacuuming effect.

Sunlaw’s artistic achievements included winning the Gold Medal for Best Original Music at the New York Film Festival for a film documenting the construction of the power plants. I wrote and performed the music. We also had a public mural program that included the “Aztec Princess” by Eloy Torrez, a cartoon by Mario Rincon, and murals by the winners of the annual Vernon Elementary School art contest.

The profits from these power plants paid for the tens of millions of dollars spent to (unsuccessfully) develop the Nueva Azalea Project.

NUEVA AZALEA

I tried to idealize Nueva Azalea from the standpoint of a child growing up in a Los Angeles so smoggy we sometimes were not allowed to go outside to play. Nueva Azalea was my gift to the world, and it is fair to say in some ways it was my baby.

I wanted Nueva Azalea to be beautiful, truly beautiful. I wanted to set an example that could anchor my dream of Los Angeles as a clean city of landmarks that celebrated diversity. I wanted to achieve the ultimate environmental and energy goals.

Had Nueva Azalea been successfully developed it would have:

- Established new standards legally binding in the whole natural gas power industry resulting in emissions levels from power plants so low the air coming out would often be cleaner than the air going in, except for carbon dioxide. And for carbon dioxide, room was specifically reserved to put in treatment facilities to remove and recycle the carbon dioxide.

- Provided low-cost energy to surrounding neighborhoods and public facilities.

- Rid South Gate of a huge truck depot, meat packing plants and other highly polluting businesses on the edge of their residential area.

- Nueva Azalea would have been visible from the landing approach to LAX, and been part of a visual quartet of architectural landmarks including Disney Hall, Getty Center and LAX.

The Nueva Azalea Project became highly controversial. Sunlaw agreed to be bound by a referendum, and when the voters rejected Nueva Azalea, Sunlaw withdrew the project and ceased development.

It has been almost 15 years since Nueva Azalea was first conceived. Critics have made many charges, many based on speculation, and Sunlaw responded with the best facts available at the time, some of those also based on speculation. With the benefit of the intervening 15 years, we can now review the speculation and determine whose predictions were most accurate. In retrospect some facts are now clear:

- Sunlaw’s environmental and social contract claims were correct.

- Nueva Azalea’s opponents were wrong. Some were sincere environmentalists acting on bad information. Some were NIMBY (“Not In My Back Yard”) environmentalists using environmental laws for tactical reasons.

- The most virulent opposition, however, arose from failure to pay bribes and use contractors and consultants specified by members of the City Council and City Treasurer who were later recalled overwhelmingly by South Gate voters, and some of whom went to jail after conviction on Federal corruption charges, and made worrisome physical threats that resulted in felony charges.

CONCLUSION

Sunlaw was a one-of-a-kind company that prospered at a unique time in energy and social history. Despite the disappointment of Nueva Azalea, the people of Sunlaw have done well after Sunlaw shut down. Thousands of kids were helped by our various community programs, and the art lives in its own special way. I have returned to music full-time, and recently completed re-writing the Brandenburg Concertos.

Monthly archive

- November 2023 (1)

- September 2023 (1)

- December 2022 (1)

- July 2022 (1)

- June 2022 (1)

- May 2022 (2)

- February 2022 (1)

- January 2022 (1)

- December 2021 (1)

- October 2021 (2)