The Midcentury Modern Challenge

The Midcentury Modern Challenge

As midcentury modern buildings reach the end of their useful lives, a number of academic institutions are having to figure out whether to restore, remodel, or demolish these structures. It's a balancing act, made even more tricky by the fact that different people have radically different responses to the aesthetic qualities of modernism. The solution is to interpret the historic and cultural value of modernism while also helping campuses fulfill their missions.

Two projects we have in process right now, one for UC Berkeley and one for Claremont McKenna College, provide some good examples of the challenges and considerations.

UC Berkeley asked us to revitalize the area around Lower Sproul Plaza, which was built in the 1960s and included Eshleman Hall; the Martin Luther King, Jr. Student Union; the César E. Chávez Student Center; and Zellerbach Hall. In the early planning stages of the project, the question was whether to embrace, integrate, and adapt, or to bulldoze.

Eshleman Hall, which housed student organizations, was in need of expensive seismic upgrades, and it was programmatically inflexible. Eight stories tall, it cast a long shadow on the plaza to the north. Its concrete and glass facade concealed the activity within. The decision was made to demolish it and replace it with a lower and longer building, five stories tall, with extensive glazing to make visible the action inside and energize the plaza. And even though the new Eshleman is lower, it’s still just slightly larger than the old one, with more flexible facilities for student organizations and studying and better access to the plaza and street.

The decision was made to save Martin Luther King Student Union because it is more flexible and had some architectural significance, although the original interior spaces had been compromised. It, too, is a robust concrete building. Semitransparent glass additions to the west and south sides will give it a more active, open public face along the plaza and Bancroft Way. An open-air covered bridge at the second level will join it to the new Eshleman. Since MLK has entries on both Upper and Lower Sproul Plazas, this new connection will make it easy to walk from Upper Sproul right to Eshleman. In essence, we have expanded the public realm of Upper Sproul through MLK and across to the upper level of Eshleman.

The Chávez Student Center will receive only minor renovations—it’s a highly idiosyncratic building, with concrete umbrellas, originally designed as a dining commons and then converted into administrative offices and a 24-hour student learning center. Despite the alterations to the interiors, the structure maintains its architectural integrity. It’s too delicate and complex to adapt very much. In our intervention, we lightly touched Chavez, creating study centers that will offer transparency on the north edge of the plaza.

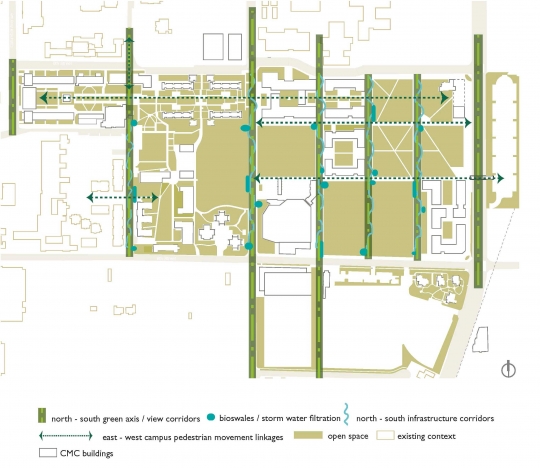

In our view, historic significance is not the only criterion for preservation—what matters most is that it’s valued by the people who use it. A case in point: a few years ago, Claremont McKenna College asked us to do a master plan for their campus. Claremont McKenna was founded in 1946, so the campus consists of post–World War II, small-scaled “modest modern” buildings surrounded by single-family homes. These buildings are beloved, although they are not historically significant—they’re modest background buildings. The newest arrival on campus was the Kravis Center, designed by Rafael Viñoly Architects and completed in 2011. The Kravis Center was modern, impressive, and big, relatively speaking. Claremont McKenna asked us for a master plan that would guide growth and balance their modest post–World War II buildings and revered landscape with their new and large arrivals.

We started by asking our clients to reflect on their values so we could imbue them in our master plan and expound upon them, integrate them, highlight them, frame them. I remember a board of trustees meeting where this all became very clear to me. We presented the early master plan development—always a tricky proposition, given the often abstract nature of the planning documents, particularly at the early stages. After the presentation, a trustee approached me and said, “I’m concerned about the direction.”

For an architect, that’s the moment when beads of sweat appear on your forehead. I asked him to say more. And he said, “I’m afraid that when I visit Claremont McKenna in ten years or 20 years, I won’t recognize it as the place I went to school. I literally won’t see it anymore. I won’t connect to what it was.” Even today, when I think about his comments, they resonate with me, because I totally relate to that fear of losing continuity with your physical surroundings. Memory is important. We had planning on removing some of those modest modern buildings for functional reasons—but we ended up revising the master plan to keep them.

Often what people remember about a campus is not a building or buildings but a landscape experience, particularly if the buildings are modest background structures. In the case of Claremont McKenna, the landscape is spectacular by anybody’s measure. There are 110-year-old California live oaks with huge trunks. So our intervention has more to do with helping create a transition between the one- and two-story existing buildings and the larger-scale buildings that the college plans to build in the future, such as its first gymnasium. We identified the best place to site these future buildings, figuring out how they should sit on the land and relate to the existing campus fabric and perimeter.

I believe that what people value in the best college and university campuses is continuity. In such cases, our eyes go the landscape because the landscape is beautifully considered, and it transitions from one level to another, or the architecture has a sensibility about texture and color that is not dogmatic but relational.

One of the challenges to consider in thinking about midcentury modern buildings is that the attitude toward their design value tends to be split generationally. The administrators, the campus architects—our slightly grayer-haired colleagues—are generally more enthusiastic about these buildings than the young students, who often see midcentury modernism as cold and inflexible.

A solution, I think, is integration. Embracing new and flexible programmatic initiatives within and adjacent to the framework of what once existed can enliven the spirit of midcentury modernism while preserving campus heritage. We’ve tried to do that at Claremont McKenna College, and I believe it will also be visible at UC Berkeley, too, in the way that the new Eshleman Hall and the renovated and expanded Martin Luther King will work together within their midcentury historic context. So much of our work is about navigating the middle ground between program, architecture, and its relationship to memory. All three have to work together. It’s all about creating a dialogue.